The most influential criticism of the excesses of the Industrial Revolution came from Karl Marx. His writings (in collaboration with Engels) embodied in Communist Manifesto (1848), Das Kapital (1867) and other pieces sought to project the process and outcome of Industrial Revolution and aftermath as a conflict between the capital as represented by entrepreneurs and the under-rewarded labour. Marx believed without the labour contribution, capital might not have been able to translate into materialistic possessions.

Marixan typology assumed the deterministic nature of an individual position in a class hierarchy. It was a product of his place in the production process. Implied in Marxian construct was deeply intertwined inter-linkages between humans as societal animal and human as economic animal. Class, to Marx was a group of inherent and common interests and there arose multiple groups often with conflicting interests. Wage maximization as objective of labour conflicted with profit maximization objective of capitalists’ thus triggering antagonism between the groups. Given the ownership of production means, the capitalists were in a position to acquire labour power. In absence of ownership of production means, the labour were compelled to offer their services to capital at lower prices. While the labour produced the goods, the appropriation of the same became the preserve of the capitalists.

Inherent in Marxian notion is an imbalance in distribution of returns between capital and labour. A shoe might be sold for $1 and given each shoe needs 15 min to produce, one can produce four shoes per hour. Sales of these shoes fetches $4 to the capital. The labour gets $1 as wages per hour. Assuming the costs of maintaining capital, land and other operational costs at say $0.5, the capital was left with $2.5 which in Marxian structure might be termed supernormal profits. Without the contribution of labour, the shoes would never have been manufactured in the first place, yet the profits were being arrogated by the owners of capital with labour having to do with subsistence wages. For Marx, an objective measurement of the value of commodity lay in calculating the average number of labour hours required to produce the same. The line of arguments became popular and continued to remain influential around 150 years post Marx.

Labour exploitation by the capital is undisputed to a substantial degree. The exploitation antedated Industrial Revolution and endures till date. The exploitation centred on the market structure for labour which was fundamentally a monopsony or oligopsony at best. Further there was high probability of employee lock-in accentuated by the presence of information asymmetry about the availability of other jobs. The intrinsic skill sets and near non-existence of mobility across skill sets worsened the matter. Cartelisation of capital often with state support implicit or explicit exacerbated the matters for labour. Trade Unions emerged as result of the same thus transmuting the individual bargaining into collective bargaining. Mancur Olson’s theory which explains best the alignment of interests by the capital given their relative lower numbers was sought to be countered by creation of group interest on the part of labour. Rather than labour being a diffused set of individuals, a collective bargaining process created a minimum needs common and inherent to every labour thus laying the foundation for the slogan ‘Labour around the world- unite!’. The structure of monopsony was sought to be transformed into a possible bilateral monopoly with mixed results.

Relative shares of labour and capital in value distribution continues to remain skewed towards capital. Some years ago, three researchers at the University of California, Irvine — Greg Linden, Kenneth L. Kraemer and Jason Dedrick — became a sort of detectives using the principles of forensic cost accounting. They decided to scrutinize all the parts that went into the iPod. iPod given its disruptive nature and being manufactured in China was near perfect candidate for investigation and illustration. Their findings demonstrated the growing complexity of the global economy thus exposing the limitations of conventional trade statistics.

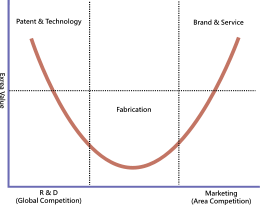

To us, however, rather than demystifying complexity, it is germane to survey the value distribution among the parts of the iPod that was priced at $299. Apple’s share of value distribution was $80, around 27% of the total price. The workers in China who assembled the iPod, thus the core labour in Marxian phraseology secured around $3 thus about 1% of the total value distribution. Given the relatively skewed value distribution, prima facie, it seems to validate Marxian assertion of capital exploiting labour. Activists like Naomi Klein seem to have been validated in their case against corporates and branding. Activism is one part of the story, yet the skewed distribution has another story to share. As Hal Varian pointed out in a context, iPod was a product of a genius who figured integrating some 451 discrete parts into making something valuable that was responsible for iPod being priced $299. The theoretical framework was provided by Stan Shih, the founder of Acer in his observations on ‘Smiley Curve’. The curve is explained in Fig. I

Fig-I Simple Framework of Smiling Curve as developed by Stan Shih (The curve is an illustration of Smiling Curve and has been adopted from Wikipedia.

A typical value chain would start with R&D and culminate in with marketing and service offerings by way of the stages of Design, Production and Logistics. The Smiling curve results in U shaped curve representing a relationship between production stages (X-axis) and corresponding value addition at each stage (Y-axis). The maximum value addition happens at the conceptual stage. Anybody can assemble an iPod or an iPad given the blueprint but conceptualizing the integration of some 451 mostly generic parts into something valuable fetches the highest value. Therefore it should be no surprise that patents, technology origination, prototype all fetch higher values. As the good in question moves through the stages, the value addition diminishes with manufacturing/fabrication commanding the least value. To add, competition is global in research and development (R&D). Anybody in the world could have conceptualized iPod and by winning the race, Apple is able to extract maximum value. Once the good is manufactured, the battle for consumer’s mind is local. More often than not, firms have to engage in hand to hand combat with competitors offering close substitutes. An outcome of this gaining consumer mind share and later desire to buy followed by actual purchase involves series of marketing activities like advertising, sales, retailing, after sales service etc. These activities thus seem to add higher value and firms engaged in these activities benefit. Preliminary analysis of electronic goods seems to indicate low value proposition.

Therefore, it is the ideas that contribute to highest value addition. Given the universality in the battle of ideas, the fact that Apple came up first gave it a head start, a path dependent move thus leads to a prospective higher share of value distribution. The production dynamics are arranged in system wherein the assembly of fabrication is perhaps the simplest process and something which is done fast to meet the ever growing demands in the market. The number of individuals who could assemble or fabricate would be higher thus lower share in value distribution. Knowledge as a factor of production something ignored by Marx and even the classical and early neo-classical economists contributed the maximum to value distribution. It is not the manufacture that underlines the economy but the ideas translated into blueprints and knowledge and appropriate through intellectual property rights are the underlying drivers of prosperity. They fetch the highest value share.

The modern economic and business thinking in the West recognized this and moved on to secure the higher shares for themselves. Theory evolves from practice. Chinese practices seek to adopt mercantilist methods of appropriation backed by significant state power. Marxians live in a universe of theory that still believes manufacturing is physical and labour intensive. Contrary to the thinking, manufacturing is increasingly a subset of knowledge driven product development and innovation process. What anecdotal and data driven evidence indicate is the limitation of Marxian understanding, Conceivably, Marxian prescriptive modelling was inherent to the times he lived. He developed theoretical model from practice but the succession ensured the reverse became the characteristic. The model might to good extent perhaps relevant in the times of early industrial revolution stages, but with passage of time, unearthing of more information makes it more limited to application and context.

Aw, this was an extremely good post. Taking a few minutes and actual effort to generate a very good article… but what can I say… I put things off a whole lot and never seem to get nearly anything done.